Erik Kwakkel confesses his love of Medieval books

As Scaliger professor, Erik Kwakkel is responsible for the academic context of the complete Special Collections of the Leiden University Library. His inaugural lecture on 15 May will focus mainly on the section closest to his heart: Medieval books.

Due to the selected cookie settings, we cannot show this video here.

Watch the video on the original website or

The physical shock of history

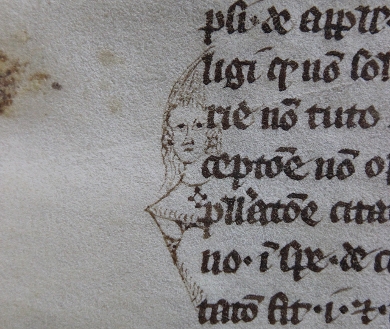

In his inaugural lecture, Kwakkel makes it clear that he is an acadamic with one foot in the tangible history of the book and the other firmly in the present day: he is an enthusiastic user of Twitter. He talks about the physical shock that handling a Medieval book - literally making contact with the past - can cause, but also about how social media reveals just how many lovers there are of antique books and how their enthusiasm is fanned by images from such works and the stories behind them. His tweets are regularly read by 40,000 people and even up to 100,000 in some cases. As well as this, social media is also a readily accessible meeting place for academics.

Used as toilet paper

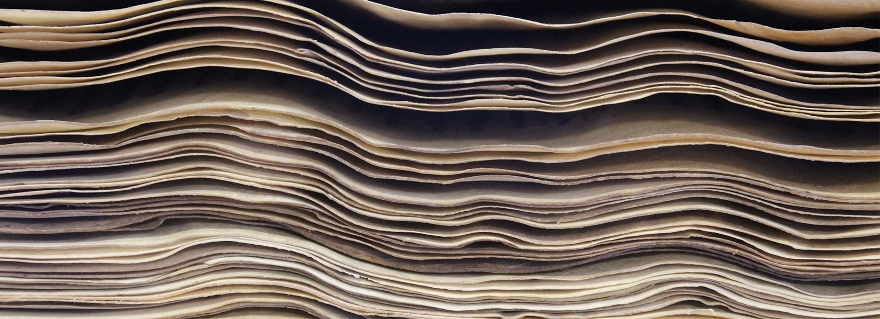

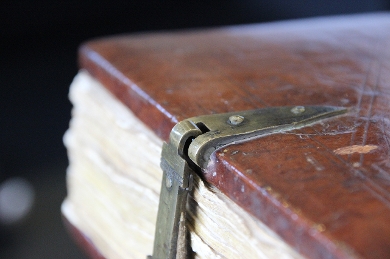

According to Kwakkel, we should be pleased that any of these old books at all have still been preserved. It could take up to a year to produce a handwritten manuscript with illustrations, a process that was enormously expensive. But what happened when the owner died and the love of books proved not to be something he passed on to his heirs? In such cases, these hand-made books were often used as toilet paper, or, in the case of parchments made of animal skin, were sold for glue and re-used as stiffening material for articles of clothing.

Emergency money

The situation changed dramatically when book printing was invented; hand-written books were used to reinforce book bindings, as recent restorations have revealed. And during the seige of Leiden, old prints were recycled to produce emergency coinage, with paper coins being cut out ofseveral pages that had been glued together. Estimates show that some 35,000 paper coins were produced, cut from 5,500 pages of around 20 books.

Usage and promotion

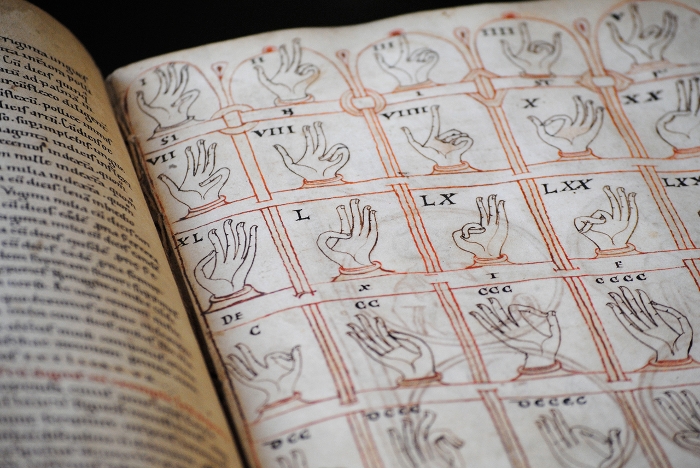

If our ancestors were so keen to get rid of these books, why should we treasure historical volumes? The first law of the library world, as Kwakkel knows well, is: storage and restoration are there to serve usage and promotion, and usage also includes 'academic use'. Kwakkel aims to start a multidisciplinary research project to discover how teachers actually taught in the past. He intends to use the educational artefacts held in the Special Collections as the basis for this research. These can be volumes that were used for teaching, as well as books with notes made by pupils or students, and even wax tablets held in other sections of the University Library. The Special Collections can offer many and diverse educational insights into the past.

Lessons from the past

Ultimately, Kwakkel believes we may well gain knowledge that will be useful in the present day, information that we can use to improve teaching today. How cool would that be?

(CH / All illustrations: Leiden University Library, photos Erik Kwakkel)